A Bird Celebration REVOLUTION is Happening Right Now in the Amazon

Fostering a love of birds through education in the Amazon, CONAPAC is increasing environmental awareness and jump-starting a birding revolution in Peru.

By Brian Landever

More than 1000 students from 26 remote Amazon rainforest communities gathered this September to participate in the first-ever bird festivals in the Peruvian department of Loreto. They awoke early, traveled to neighboring communities along the Amazon rivers, and spent the days presenting elaborate performances related to bird conservation and discussing the impact of birding in their communities.

Activities celebrating birds and birding have gained momentum since 2017, and a revolution is building. It’s a celebrative kind, raising spirits and enhancing the cultural arts. Children are showing excitement for the natural world, and their parents are following suit. It’s in good time; Peru has been listed as the world’s best country for bird watching, and is second worldwide for most species of birds registered. Most importantly, these activities are showing concrete increases in bird conservation.

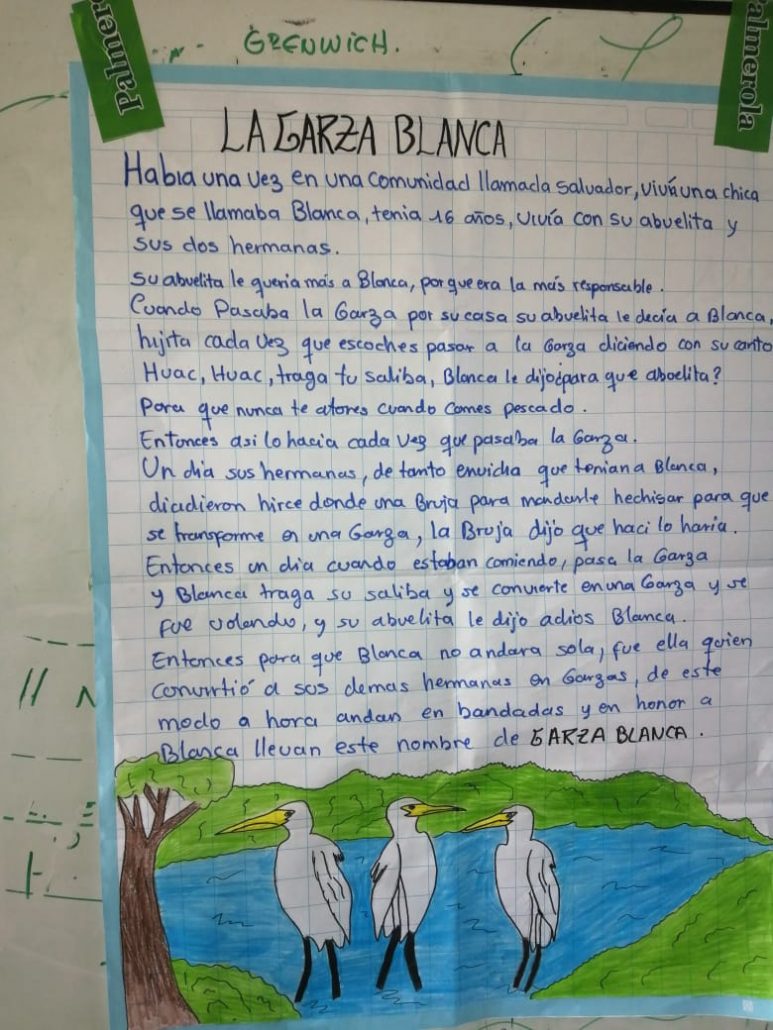

The people in this region are strong, accustomed to the intense Amazon sun, and mainly fish and grow crops for sustenance. Children and adults cheerfully play sports every afternoon, and couples help one another with fishing. Their music with flutes, drums, and rattles, their regional dances related to animals, and their stories about the meanings behind bird encounters are just a few aspects of the people’s rich culture. Their homes may not have electricity or running water, and are over 100 kilometers from the closest city, but the warmth and comfort they have amongst one another in communities makes international visitors appreciate coming here.

Although many visitors return frequently, until recently, the forest was not commonly explored for leisure; entering only when hunting was the priority. That’s all changing now. Now, there’s a greater awareness of how the birds are important to the environment, developing the people’s pride for their home.

Education is key

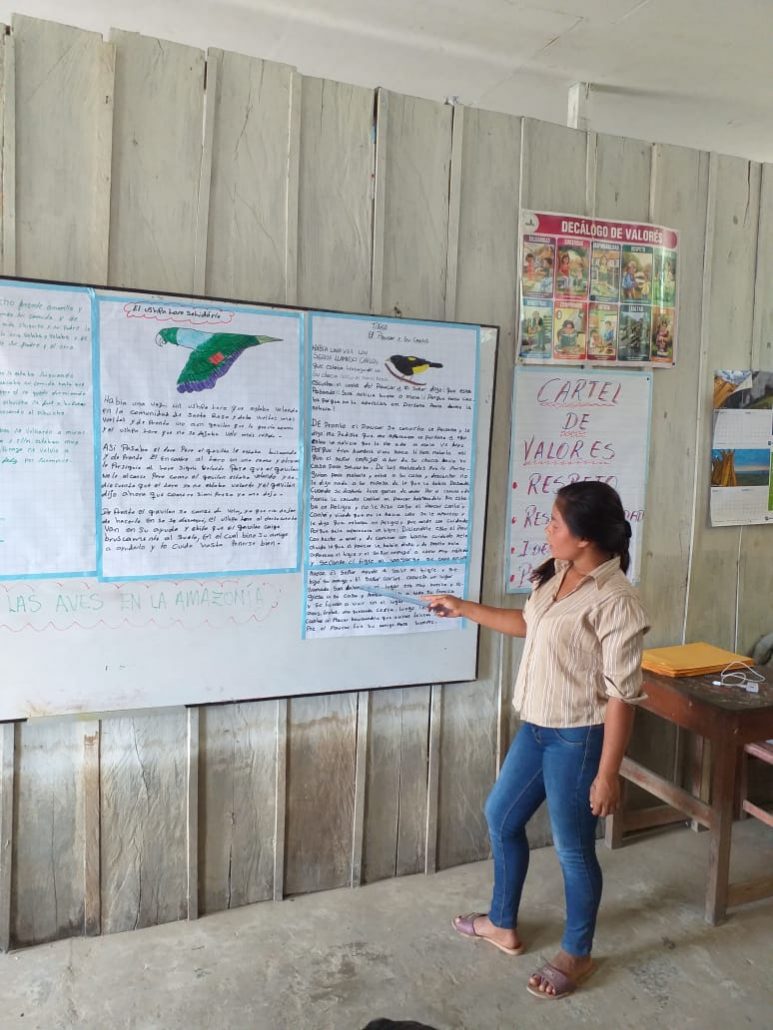

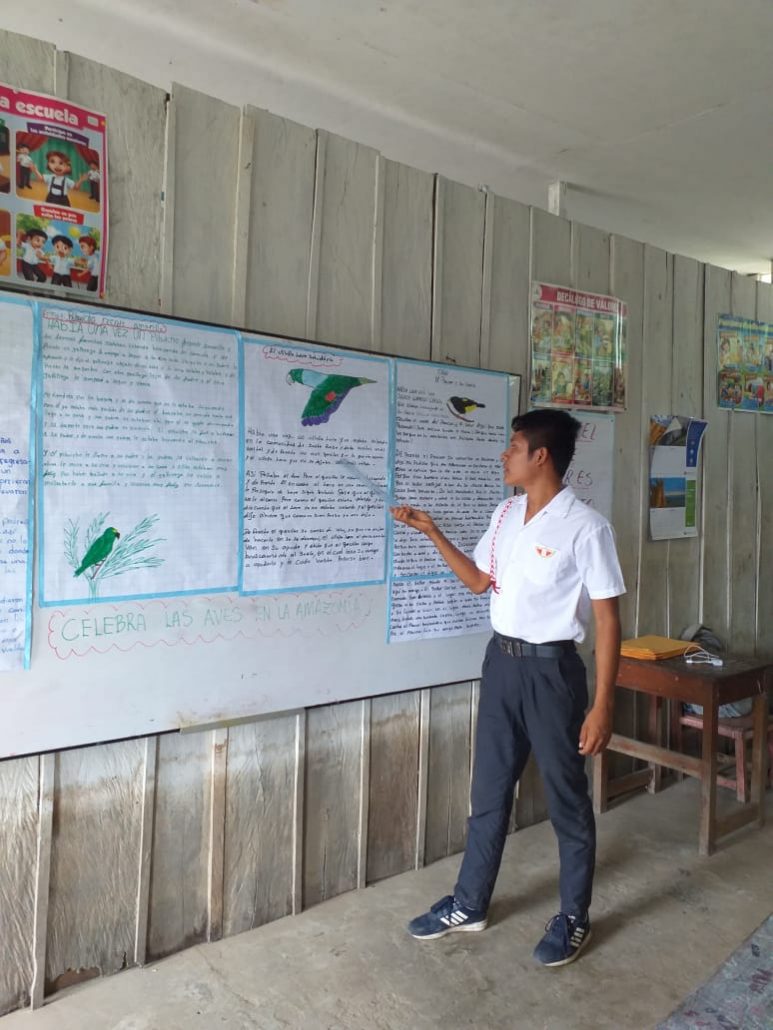

Thousands of K-12 students became involved in this movement over the past several years. Their teachers are leading outdoor, project-based classes to inform them of the region’s bird species’ habitat, behavior, nesting, diet, cultural stories, and more. And their new curriculum is paying off.

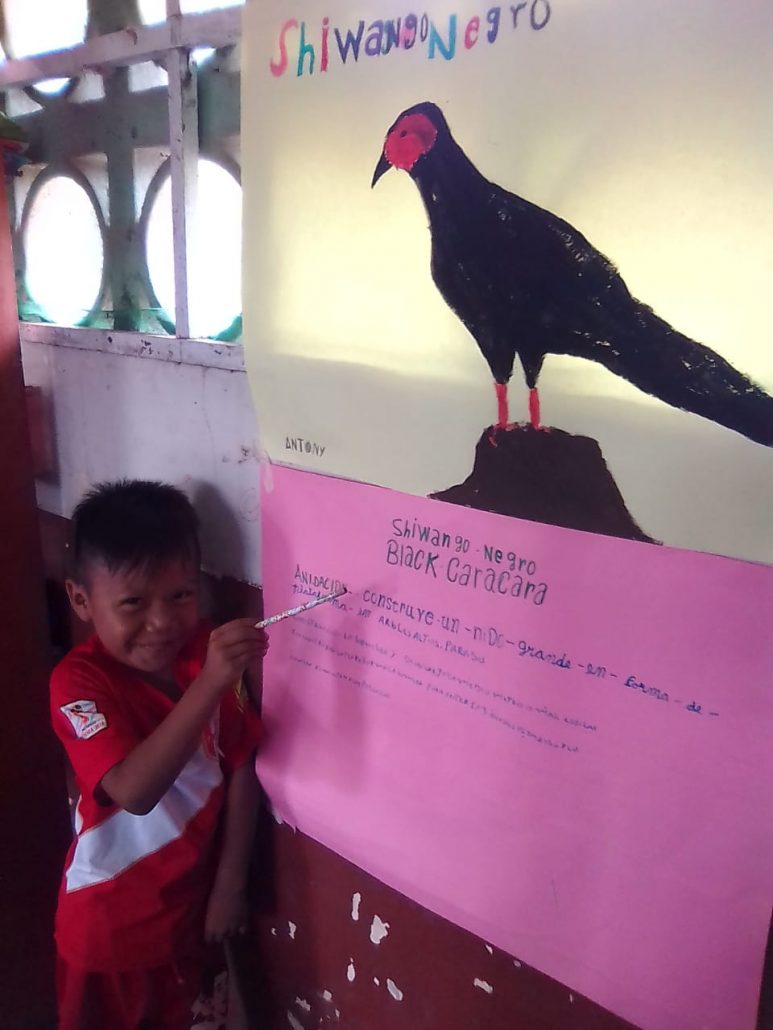

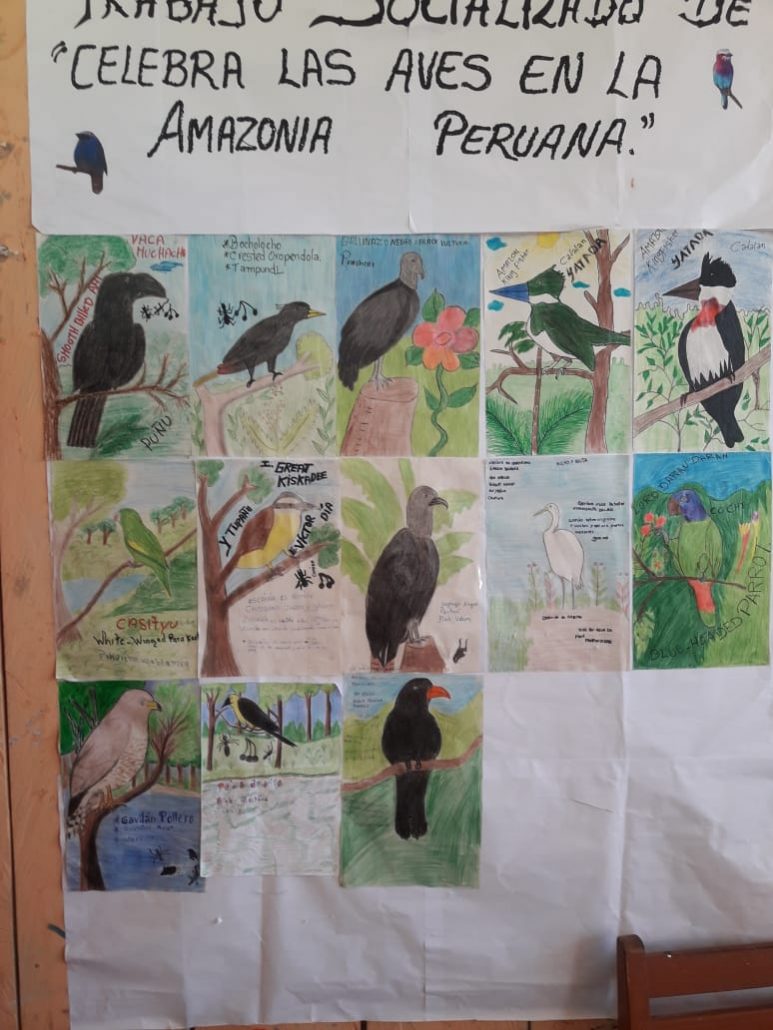

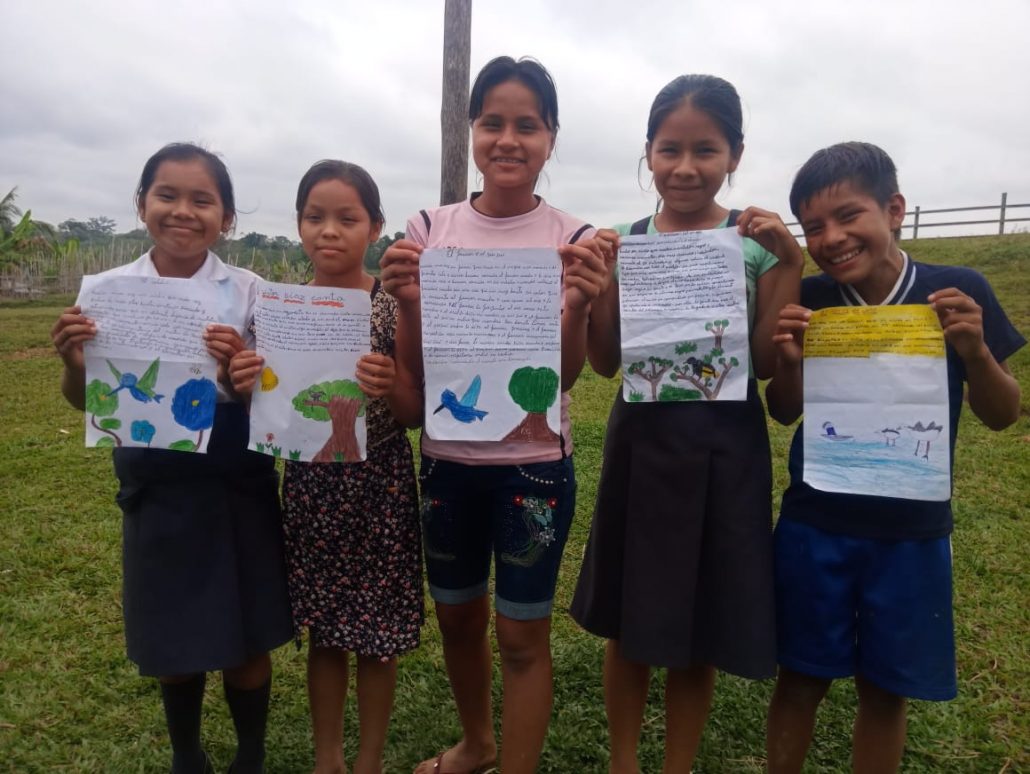

During these festivals, students share what they are learning in unique ways. Some students perform activist theatre, portraying stories of birds fighting to retake their habitat after being encroached upon. Other students draw finely detailed portraits of the birds with masterful skill, and still others have crafted replica bird nests to explore nest functions. One high school senior rapped about birds’ beauty and the tragedy of losing them. Another 14-year-old young woman’s dramatic poetry about respecting birds in nature left watchers teary-eyed. Groups of younger students were happy to be included too, sharing well-practiced songs about birds’ beauty. One mother even rose to share an unsolicited folk song about the Blue-gray Tanager.

The impact of this is visible. Children are heard stopping their classmates from killing birds, and their parents report no longer hunting birds in unsustainable ways.

Behind these activities are 250 dedicated teachers, Peruvian NGO CONAPAC, led by Brian Landever, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (CLO), represented by Karen A. Purcell and Marilu López Fretts. They have been co-creating training workshops each year since 2017, resulting in dozens of dynamic lesson plans, materials, communication methods, and culturally embedded evaluations all focused on keeping enthusiasm strong.

Building a revolution

In 2017, the first ornithology training workshop was held for teachers from these rural communities. Karen A. Purcell and the “Celebrate Birds” citizen science team began co-developing materials, and soon launched an engaging, fun, culturally sensitive educational program focused on bird conservation.

In 2018, teachers began notably increasing their involvement following bi-monthly meetings with the CLO team. The large WhatsApp group began to receive hundreds of photos posted weekly by the teachers, excited to share their progress, in turn motivating one another.

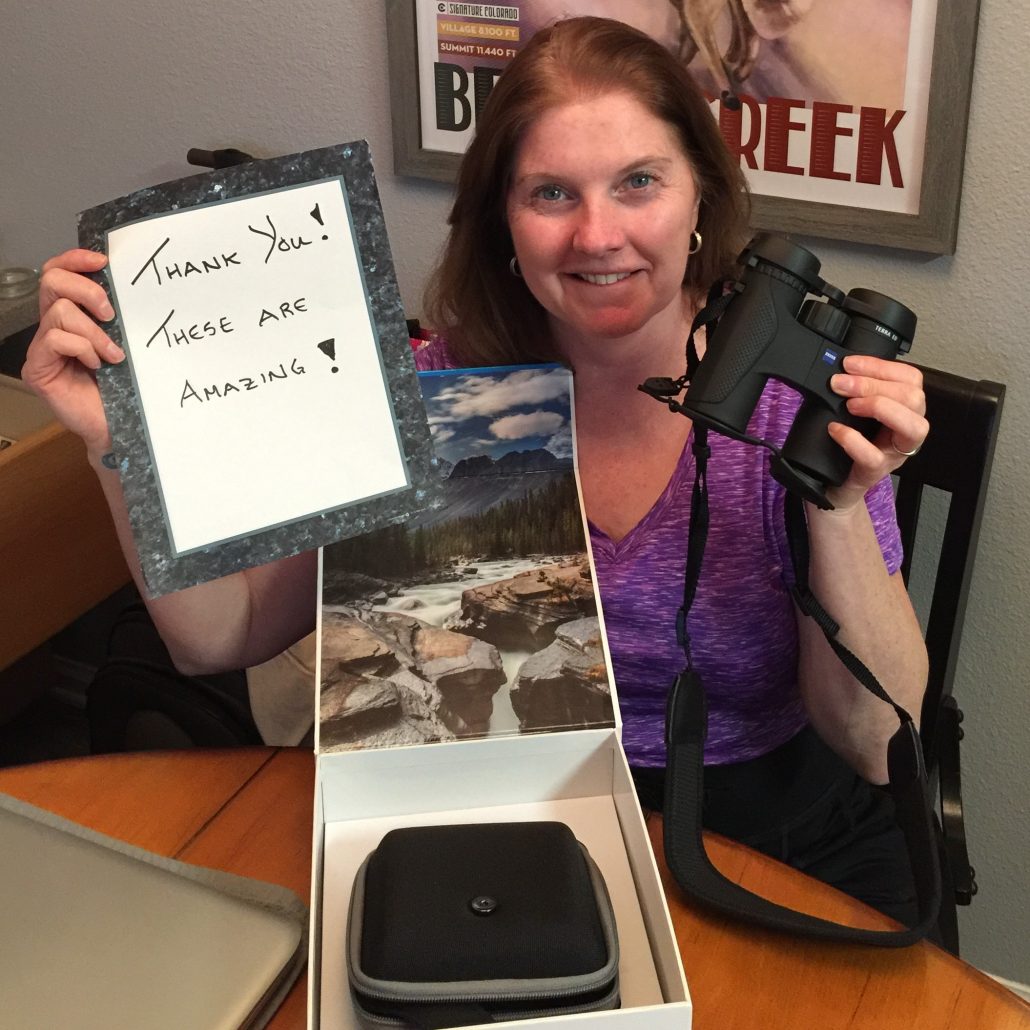

In early 2019, there was no doubt that the program had matured when students presented unsolicited, elaborate skits and dances related to bird conservation during CONAPAC’s visits to their communities. Thousands of photos of class developments began to fill the WhatsApp group monthly, and the program supporters, JBQ Charitable Foundation and the Amazon Binocular Project, have stated they could not have used their donations in a better manner.

When the last workshop was held in June 2019, at Explorama’s lodges, located on the Amazon and Napo rivers, the teachers themselves opened the event. They had prepared creative songs, photo-realistic sketches of birds, and enthusiastic presentations of what they had accomplished to date with their students. The entire week was festive, productive, and further prepared the teachers with strong class curriculum. CONAPAC’s footage of these classes on its YouTube channel effectively capture the enthusiasm of these events.

In turn, the students are receiving motivated class sessions and can see that they have become part of something that is expanding, and being appreciated worldwide. The culmination of this, five bird festivals that took place in September, has surpassed everyone’s expectations.

Moving forward

During these festivals, the perspectives of local people were inquired into more closely in open conversations following each morning’s presentations. Discussions amongst parents, community authorities, students, and teachers with CLO are building an understanding of the movement’s impact on people’s lives and environment.

New, exciting initiatives were also shared during the festivals, including long trails, or “senderos,” complete with benches and gazebos, built by parents for children to birdwatch in the forest, building their understanding of how birds live in nature.

Right now, thorough, co-created program evaluations are being led by CLO to analyze the progress being made. The classes continue regularly, and bird clubs are meeting regularly amongst the most interested students from each community. Eight birdwatching trails have been developed, and more are being planned. The first community-led bird festival in Loreto was held on October 30th, 2019, uniting 11 communities and 600 people, leading to a press report.

The potential for this program to have a positive environmental and social impact is clear. As it gains more attention in Peru and internationally, it will add momentum to the global movement to respect and conserve the Amazon rainforest. For bird appreciators, incorporating ongoing citizen science data from students and community members will expand the database of birds from this region on Cornell’s eBird.com. If the Peruvian board of education replicates the training and materials in other areas of Peru, the impact would multiply tremendously, further fueling the country’s strong efforts to be a prime tourist destination. If more bird festivals occur, celebrating birds could become a proud new tradition.

Nonetheless, what has happened over the past three years has given unforgettable, enjoyable memories to thousands of children in Peru, empowering them with activities that contribute to the wellness of the Amazon rainforest and the planet overall.

Brian Landever is Director of Conapac, devoted to conservation and community development, in Iquitos, Peru.