Birding in Papua New Guinea

By Avery Phillips

Victoria Crowned-Pigeon (Goura victoria)

Papua New Guinea is known for its diversity, in terms of landscape, culture, and species of birds. With rugged mountains, tropical rainforests, large wetlands that almost 800 different species of birds — 76 of them endemic — call home, this island country is an ideal place for birding.

Because of its mountainous interior, Papua New Guinea does not have much in the way of infrastructure. Some locations can only be accessed by helicopter or on foot, so get your gear ready. A sturdy backpack for camping, a good pair of binoculars, and a solid pair of hiking boots will do the trick.

You may also want to brush up on your photography skills and bring your camera along to document the scenery and avifauna on your adventure. You want to be ready to photograph one of the many species of pigeons, kingfishers, or birds of paradise.

Keep your camera out; in addition to the plethora of unique birds, Papua New Guinea has gorgeous scenery and landscapes you’ll want to capture on film as you work your way through the mountains, forests, and rivers. And who knows — maybe a flock will take to the sky as you’re positioning your camera for a shot! With some planning, a lot of exploring, and a dash of luck, you may be able to catch a glimpse of one of these unique birds that live in Papua New Guinea:

1. Victoria Crowned Pigeon

The Victoria crowned pigeon is one of about 40 species of pigeon found in Papua New Guinea. It is a ground-dwelling bird recognizable by its blue and white crests, maroon breast, and red irises. They are typically found at sea-level in lowlands or swamp forests and fly from the trees to the sea daily.

Victoria crowned pigeons search for food on the forest floor, often in small groups or pairs. Fallen fruit is the staple of their diet, though they will occasionally eat seeds or small insects too. Though they are widely kept in captivity, they are the rarest species of crowned pigeon found in the wild — and definitely worth seeing while birding in Papua New Guinea.

2. Shovel-billed Kookaburra

The shovel-billed kookaburra, also called the shovel-billed kingfisher, can only be found in Papua New Guinea. Their bills are short and broad, and they have dark heads, a white throat, brown irises, with rufous coloring behind their eyes, on their neck, and underparts. They also have a bright blue rump, and males have a dark blue tail while females’ are rufous.

Shovel-billed kookaburras primarily live in hill forests, though they have been sighted at sea level and elevations up to 2400 meters. Though they are not endangered or vulnerable, they are thought to be crepuscular or partially nocturnal, making them difficult (but not impossible!) to spot.

3. Black Honey Buzzard

A bird of prey endemic to the island of New Britain in Papua New Guinea, the black honey buzzard inhabits subtropical or tropical lowland forests and tropical mountain forests. They are known for their almost entirely black plumage with distinct white bands on their flight and tail feathers.

Not much is known about the black honey buzzard, but they are classified as a vulnerable species by the IUCN Red List due to habitat loss. Though rare, they are easiest to spot while in flight because of their white bands.

4. Pesquet’s Parrot

Pesquet’s parrot can be found in hill and mountain rainforests in Papua New Guinea. They are large birds, with black plumage, grey scalloped feathers to the chest, and a red belly and wing-panels. They are sometimes referred to as the vulturine parrot, because of their long, hooked bill.

These parrots feed almost exclusively on different species of figs, and their bare head prevents the sticky fruit from matting their feathers. Though they are considered vulnerable due to overhunting and habitat loss, they are typically spotted in pairs or up to groups of twenty birds, making them more conspicuous than other elusive birds in Papua New Guinea.

5. Raggiana Bird of Paradise

This list wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the famous birds of paradise that populate Papua New Guinea. The Raggiana bird of paradise is the national bird of Papua New Guinea and is included on the national flag. They are widely distributed in the south and northeast, typically in tropical forests.

Raggiana birds of paradise are maroon to brown, with a pale blue bill, and light brown feet. The males are more majestic than the females, with a yellow crown and collar, dark green throat, and long tail feathers, which range in color from red to orange. They are known for spectacular courtship displays — hopefully you’ll be lucky enough to stumble upon a lek!

***

These are only a few of the hundreds of amazing birds that inhabit Papua New Guinea. To learn more, check out the Asia Membership, which provides in-depth information and images for most of the 1700+ species in Asia, including those of Papua New Guinea. However, there’s no better way to experience the avifauna of this nation than to go birding there yourself.

In the Eye of the Storm: How Birds Survive Hurricanes

By Juliana Smith

Hurricane season strikes the Eastern seaboard of the United States every summer and, guess what? We’re in it right now! The season begins in June and runs through November, but as we here on the East Coast know, storms can arrive as early as April. While hurricanes often conjure images of wind-torn towns and flooded highways, their impacts on wildlife are less impressed upon human minds. However, wildlife also experience the forces we humans contend with, and birds are no strangers to hurricane season.

Being a lightweight, feathered animal has its perks (ahem, the ability to fly), but can also be incredibly debilitating when faced with extreme winds. Unfortunately, hurricane season coincides with Fall migration, so many birds are forced to face these powerful storms head-on. Yet, despite the odds, bird populations largely succeed at weathering the season. Of course, not every avian individual or community survives hurricanes, but in general, it appears birds have developed four tactics to help ease them through the stormy spells.

When a storm is on the rise and headed our way, we have weather forecasters and doppler radars to warn us of impending natural disaster. Birds, while not equipped with our high-tech gadgets, can sense that trouble is nigh when they pick up on the drops in air pressure that precede storms. Some birds take their cue and surf the headwinds of the hurricane, using them to get them out of dodge as quickly as possible. If conditions are right, migrating birds can even use the storm’s headwinds to get a wing up on their migratory journey.

Other birds, though, might use the eye of the storm as a refuge during a hurricane. This tactic seems to be especially popular with seafaring birds, though there’s no way to confirm their intent. Birds caught up in the storm might chance upon or follow winds to the eye where things are calm. Once there, they are effectively trapped, or “entrenched”, at the center of the hurricane and will follow it until the outer spiraling winds weaken, much to the delight of birders. Entrenched birds often wind up hundreds of miles from their home habitat, creating a fallout of rare sightings in inland habitats. Groups like Team Birdcast hope to utilize these events paired with eBird reports to better understand the relationship between hurricanes and birds.

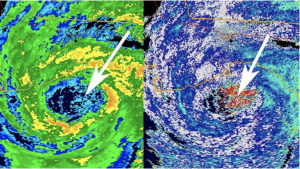

Hurricane Hermine (2016) doppler radar imaging. The red blotching in the right image is a flock.

It’s important to understand that displaced birds shouldn’t be disturbed. While it is definitely better to be within the eye of the hurricane than be in the spiral, eye riding, as it’s sometimes called, isn’t exactly relaxing. It not only forces birds hundreds of miles from their home habitat, but can deprive them of food and rest for many days at a time. Those that survive until the storm dissipates then have to make a long return journey home. Even with the risks, though, it certainly seems safer to seek refuge in the eye than fight the storm.

And yet, some birds have done just that, flying directly through storms. We’ve only recently stumbled upon this behavior thanks to satellite transmitters and some spunky whimbrel . In 2011, researchers were astonished to find that one of their tracked subjects, a tagged whimbrel, had actually forced her way through Hurricane Irene. Since then, other members of the same species have been recorded using a similar tactic to survive hurricanes. Interestingly, researchers believe that migration is one of the factors allowing these whimbrels, and unknown others, to push through. Before migrating, birds will beef-up and pack on as many fat stores as possible to help supply them much-needed energy through their long migration routes. Researches believe it’s these fat stores that give some birds the power to fly straight through nature’s most wicked storms.

While some birds are skirting, riding, or cutting through hurricanes, others are hunkering down at home. Equipped with a clamping back toe, passerines are capable of weathering hurricanes by clinging to tree branches or seeking refuge in tree cavities. This author has even witnessed a small flock of house finches huddled under stowed kayaks to hide from Tropical Storm Irma in 2017. Tree clamping through a hurricane has its obvious risks, especially if your chosen branch is knocked from the tree (or your kayaks get flooded), but it also preserves fat stores and reduces risk of getting blown hundreds of miles from home.

In the end, different birds take different measures to survive hurricanes, but all of the methods showcase avian tenacity and perseverance. They truly are remarkable animals capable of seemingly impossible feats.

Finding Scaly-breasted Munia

Nutmeg Mannikin was added to the ABA list in 2013. As of Aug 2014 their name in Clements/eBird will change to Scaly-breasted Munia to bring our North American terminology into line with that used in the rest of the world. These birds are also called “Spice Finches” in the pet trade. I’m still getting used to the new name so my apologies if I throw a few “Mannikins” into my description below!

In California Scaly-breasted Munia Lonchura punctulata: Scaly-breasted Munias are locally common in San Diego, Ventura, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Los Angeles Counties especially in riparian habitat. They also occur locally in the south San Francisco bay area and a few other scattered locations. They are common in the Houston, TX area. They also occur in Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Riverside and San Bernardino counties, although they are generally less common there.

Scaly-breasted Munias prefer riparian vegetation especially around the edges of water, such as reeds and reeds mixed with grass. They are closely associated with tall seeding grass and other seeding plants. Learning their distinctive calls will make them much easier to find, as they often remain hidden in vegetation and can be inconspicuous.

Scaly-breasted Munias are somewhat seasonal in Southern California, which is a bit odd since they don’t migrate. Munias are easiest to find between June and November and are a bit harder to find between January and April. It appears that at least some of this seasonality is related to dispersal away from breeding areas and changes in habits. Outside of the breeding season, munias tend to stay low in vegetation and are best found by their calls.

Most of the locations described below are allso good places for general birding.

Huntington Beach Central Park: A premier vagrant trap in Southern California. Scaly-breated Munias are one of the most abundant species in the wetter portions of the park, especially in the eastern portion of the park (east of Golden West Blvd). Look for them along the north and east side of the ephemeral lake in the eastern portion of the park. This is perhaps the easiest place to find this species.

San Gabriel River in Pico Rivera: A thriving colony of Norther Red Bishops (formerly known as Orange Bishops) and Scaly-breasted Munias is in the weedy grasses going to seed, upstream side of Whittier Narrows Dam flood control gates. Directions: Park near here. From the parting area, take river trail/bike path north, up and over the dam and down into the river bottom right in front of the gates. This area is often damp and full of seeding grass, and attracts large numbers of seedeaters including buntings, munias, bishops, grosbeaks, blackbirds, towhees and sparrows.

Peck Road Water Conservation Park: A colony of Norther Red Bishops and Scaly-breasted Munias lives at the North End of the lake and also near the narrow canal that separates the North and South Lakes. Note that this area is marked “No trespassing” and also has an active homeless encampment, so enter this area with caution and at your own risk. Do not go alone.

Note that this is a great area to find seedeaters of many types in the fall. A more accessible area to check is west of the main parking lot.

Lower Los Angeles River – the stream side vegetation and reeds both south and north of Willow St are good places to look for Northern Red Bishops and Scaly-breasted Munias in the breeding season.

Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park (currently CLOSED July 2014) – the reed beds around the edge of the lake host Scaly-breasted Munias, although they are harder to find here than at the locations listed above because they tend to stay in the reeds.

Rio Hondo at Rush St. – the small reed beds in the channel and the riparian edge in the 1/2 mile between Rush and Garvey. Park on Rush Street and walk west to the bike path along the Rio Hondo. Check the riparian edge and the walk north along the bike path.

5 Peters Canyon Rd, Irvine, CA. – Park across the street in the business park areas and walk across the street to the Peters Canyon concrete walled wash that runs parallel to the street and if you walk 100 yards (and typically way less) up stream or down stream and don’t see a Munia, you may have your eyes closed!

Please let me know if you notice anything that needs to be modified on this page.

David Bell 2014